Singlespeed waywardness 🇳🇮 🇭🇳 🇸🇻 🇬🇹 🇧🇿

I crossed a lot of borders in this post and I feel like there’s so much to write; it’s a long post. I managed to ride through all of the countries in central America and I now write this update from Flores in northern Guatemala. I had looked forward to Central America for a long time. Learning Spanish and chatting with people remains my favorite part, but the increased population density has also meant a lot more traffic. It’s been a fun stretch but I’m looking forward to some more rural tranquility in Mexico and beyond.

On another note, these four Central American countries have at times featured an obscene amount of roadside trash. You name it, old television sets, toilets, car parts, the list goes on. I know this in part to be a symptom of poverty; waste management costs money, money that these countries choose to allocate elsewhere out of necessity. It’s all too common that I get passed by a bus or a car and I see a hand come out of the window and let go of a plastic bag. “Ciao! Not my problem!’ Elsewhere along the roads there seem to be communal dumping sites where large quantities of trash are left. In the mountaineous regions these roadsides eventually erode and you find otherwise beautiful valleys with the occasional hillside totally strewn with trash. You then find yourself in a touristy place where there’s some kind of beautiful natural attraction, often a volcano in these parts, and loads of foreigners eager to see that attraction (I’m one of them). Because institutions like a National Park Service are not strong or at all present, the trails are often poorly develeped and overused. There are local tour operators that seem to be totally focused on maximizing paying customers with insufficient care for the environment. This has been an observation ever since Torres del Paine in southern Chile and has led me to a personal conclusion that I’d rather avoid travelling to developing countries to visit nature. There’s plenty of beautiful, well taken care of, and accessible nature where I’m from. Additionally, of the long time travellers that I’ve met, those travelling by faster means (e.g. vans and motorcycles) often complain of a sort of weary fatigue driving from one touristy volcano town to the next. I’m also at times tired of traveling but it’s the people I chat with along the roadside in no-name little towns that sustain me and are the most interesting and rewarding aspect of this trip. Waving to a man standing in a field, getting a laugh, a smile from a lady passing by in the back of a pickup truck, or a thumbs up from a well dressed old man waiting on the bus. A few examples from these past several days. I wondered where the well dressed man was headed.

Lastly, as a final example, a lot of the pictures you’ll see in this post are carefully taken so as to avoid having litter in the frame. If you were to have been present during the awesome night time shots of the volcano, a simple 180 degree turn would’ve put you face to face with a large pile of trash. It’s a reality that I wanted to point out.

Northern Nicaragua

After four or five days of resting in León I left the city feeling more tired than when I arrived. I had taken some time off to do a few touristy things in and around town but felt both physically and mentally exhausted when I hopped back on the bike. I hadn’t been feeling super great before León and was in a bit of a mental slump; sometimes the trip can become routine and if paired with enough difficult days I can really begin to question what exactly it is that I’m looking for out here. So with that on my mind, I left the city in the late morning and rode toward a far-off intersection.

Daniel and his wife on a billboard at a substation

The sage, older Austrian cyclist with whom I’d camped at the Costa Rican/Panamanian border had recommended the mountains of northern Nicaragua as one of the most interesting parts of his trip, away from the “gringo trail,” he’d told me. On the one hand I wanted to just make some progress, stay in the flats, and continue straight to Honduras, but on the other hand I was also curious about this less well-travelled part of the country. I continued delaying my decision until I made it to a convenience store at the intersection where I had to pick. I bought a drink and chatted with a man in a bus stop who was from the city of Estelí in the mountaineous north; he recommended I continue that way, “it’s beautiful” he said. It was enough for me to go off of, I wished him a nice day, and continued on the bike. For the next two days I found myself cycling in a westerly direction into some pretty strong headwinds; it was challenging but at least it was refreshing.

Please wake me up if you guys go out on a call

The first night after having left León I made it as far as El Jicaral where I cycled past a firehouse sometime around 17:30. I turned back around to chat with the guys outside and to ask about a place to camp. Again, it was no problem to set my tent up behind their building. We all chatted out back for a bit and looked for a spot without ants (suprisingly hard to find here). Before I’d had the chance to setup my camp a few heavy rain squalls passed through and we decided it was probably best that I camp in the garage. I was invited to have dinner with them we and chatted some more before turning in for the night. The following morning we all had breakfast together, the guys prepared to end their multi-day shift, and I hit the road.

More roadside trash

It was Good Friday and everything was closed as I continued into a fierce little easterly wind. For the next few hours I settled in on the bike, rested on the handlebars, and just watched the cranks spin below me. I made it to a big intersection near San Isidro and made a 90 degree left turn; finally the windy part was over. I rode through two fairly large towns but found nearly everything closed with just a few people out and about. I rode on and eventually found a small convenience stoor with an open door. I walked in to buy some things and chatted briefly with the lady working there (it was also her house). She told me that she wanted to help me by fixing me a plate of food with sardines (Good Friday), tamal, beans, avocado, and rice. It was a nice moment, I was appreciative for the food, the company, and the boost. I jumped back on the bike and continued on a bit longer that day, eventually making it to another intersection. To the left, up a long ascending road, I’d heard there lived a man who’s spent the last forty years sculpting religious scenes into a cliff face. Going straight would take me on an easy road to Estelí, the biggest city in the area. There was a small building with a universally understood coffee cup sign hanging by the door. I asked the lady if she had any coffee, she said she did but I’d have to wait for her to make it. “Tranquilo, todo bien,” I said, I’ve got nothing but time. I asked her about the sculptor and she told me it was worth a visit. I asked her if there were places to camp up the hill to which she said “no, not really, but you can sleep here if you’d like, there’s a spare bedroom and everything. Have a seat, here’s your coffee, there’s basketball on the TV.” She invited some family over and I chatted with her son as we watched Marquette play NC State. We ate dinner together and had some coffee as they asked me about where I’m from and what life is like there. I thought about how incredible it is that I get to end up in these funny, serendipitous situations and how amazingly hospitable people can be.

Sandanista sign at the entrance to San Isidro

Watching March Madness basketball at Maria-Ines's place

Riding the bus up the hill

The following morning, Maria-Ines, the lady at whose house I had slept told me there was a bus I could take up the hill if I wanted to avoid a morning of steep climbing. The literal big yellow school bus pulled up outside and honked its horn as I quickly collected my things and we lifted my bike and myself into the back of the bus. I was off and running up the hill. Finally, it was a bit cooler up high. I bought some water from a man in a small shop and we talked about the ranchera music he was playing. A few kilometers up some steep roads, I made my way to Don Alberto Gutierrez’s finca. I had the place to myself and chatted with the sculptor and his family about the project; we had some lunch together and then I could finally descend into the city of Estelí. By this point the roads were quite bad and one of my bags managed to rattle its way off of my bike; a man waved me down and I retrieved my bag. The roads in this region were some of the worst I had seen in a long time. Imagine cobblestones but the stones used are not uniform, rather, they’re jagged and pointy and make for a rough and bumpy ride.

Don Alberto's work

An elephant

More sculptures

More of Don Alberto's work

The man himself

A lion at Don Alberto's

A chapel at Don Alberto's

I cruised through the city of Estelí, had a coffee, and kept going. On my way out of town I saw lots of tobacco fields, drying houses, and cigar factories. Only then did I remember how much Nicaragua is known for its cigars. I enjoyed the smell wafting through the drying houses and continued on into the Miraflor Natural Reserve as the roads continued to deteriorate. I remember that day as tough but uneventful. Toward sundown I stopped at a few farms to ask if I could pitch my tent on their land. At the first farm where I asked the man said he was only the caretaker and not the owner, I told him I didn’t want to cause him any problems and carried on. A second man sitting on his porch simply didn’t respond; I’m not sure what that was about. But a third man named Francisco-Javier asked me “we’re all human, no?” and told me I was free to camp on his porch. I met his wife and four of his sons and we spent most of the night chatting over some bowls of Gallo Pinto (beans with rice) and cheese. One of his sons was in his early twenties and we chatted about work. He told me that you’re lucky if you can find any around here and it pays about 300 Cordoba (US$$ 8) per day. If you work 30 days per month, which you probably will, you’ll net about US$ 250 per month.

'Where land, God, and the hands of man unite,' at the tobacco plantation

The sun going down, looking for a campsite

By now the parents were about the house taking care of a few things as I sat and finished my food with the three youngest boys. The two older boys of about eight and five shared a seat and ate their food as the younger of the two was more interested in annoying his brother. The mom yelled occasionally from the kitchen for them to quit fooling around and to eat their dinner. All the while the older of the two gently took care of their one year old little brother. We played with some connectable pogs (i.e. “flippo’s”) and built some structures all the while unable to shake the thought how unfairly divided things are; globally that is, because the kids were pretty good at making sure I had enough building pieces for the crown I was making. But in all seriousness I wondered about how much of a difference an extra $500 per month would make for this family while there’s an upper crust in this world that wouldn’t think twice about spending that much. I awoke on the morning of Easter Sunday having slept very well out on the porch as a kid came by to buy some bread from the small shop that the family runs out of their house. It all looked so similar in that moment as I imagined that the kids mom gave him some money to hurry up and buy some extra bread for breakfast. I packed up my things, walked into the field to thank Francisco-Javier for his hospitality, and hit the road. It’s been the experiences like these that have left the biggest impression on me.

The rough roads shortly before my crash in the Miraflor Natural Reserve

The road was really bad now and I stopped to try to document just how bad. I chatted briefly with a German/Italian family that lives in Teguchigalpa, Honduras but it was an otherwise uneventful morning. About two kilometers from where I knew my bumpy road would reconnect with smooth tarmac I had a head on collision with a motorcyclist. It was a long, sweeping left hand turn coming down a hill and the easiest road surface to ride just so happened to be on the left side of the road. We saw each other well ahead of time and both braked significantly but it was one of those moments where we both locked eyes and kept turning into each other; eventually we crashed and we both fell. Litigiously, my first thought when I hopped to my feet was not to say “perdóname” (i.e. “forgive me.”) but the group of people that I crashed with was immediately very helpful and worried about my wellbeing. They were four people travelling on two motorcycles. I jumped around a bit to make sure I was still in one piece. My glasses were broken and my bicycle was pretty badly bent; the front wheel didn’t turn anymore. One of the ladies from one of the motorcycles helped me to clean my cuts with the stuff I’d bought after the first crash; some hydrogen peroxide and some iodine spray. One of the guys was also a cyclist and helped me look over my bike; we had to remove the front brake so I’d be able to ride the bike again; in some way the fork was bent and the front wheel woudn’t spin with the brake installed. We looked over the motorcycle and they had to bend the handlebars back into shape. It turned out that the road was indeed just about a kilometer or two away; I was so close. One of the guys rode down to the road with me to help me find a ride back to Estelí. This would be the best place to see a doctor, get the bike fixed, and recover. Once we slowly made it back to the main road, riding the rear brake the whole time, the guy saw his neighbor who could give me a ride in his pickup truck. We exchanged numbers and he even offered me a bed in his house where I could stay. I’d end up not taking him up on the offer but I found it a nice gesture.

My bent fork

Sometime around sunset I arrived back in Estelí in the back of the pickup truck. I thanked the man for the ride, we lifted my bike out, and I rode to the hospital. I waited for a bit and was eventually attended to by a doctor. “The eyebrow doesn’t need stiches and your leg isn’t broken.” An assistant helped to clean and dress my wounds. Returning to the doctor seated behind the desk I asked her if I owed anything, she chuckled and said “no, you’re free to go.” It was dark as I rode back to the main square in town looking for a hostel. I found one that fit the bill, checked into a bunk, and sent a message to my family that started with “I’m fine, but…” It felt embarrassing more than anything. Just a few short months since my first serious crash and here I was again.

I slept in as best I could the next morning and then stripped all of the bags off of my bike. I rode to the bike shop that was recommended by one of the guys from the crash. They said they could help me make it rideable again; “come back later to pick it up.” Later ended up being the following morning when I rode the bus back to the shop. They made the bike rideable but a proper fix was beyond their abilities. They bent the fork back a bit and shaved a bit of metal from the front brake mount. I bought a few small maintenance items that I needed and rode the bike back to the hostel. The bike strongly pulls left now; this on account of the left fork blade being pushed forward.

My bike in pieces

For the next week I stayed at the hostel in Estelí as I tried to work out how best to continue with the bike and to give my body some time to recover. People came and went at the hostel as I stayed. I’d wake up and sit at the edge of the bed, preparing to limp over to the bathroom, as I began to really wonder what in the hell I was doing out here. Is this all really worth it? When I was still working I’d read lots of books, watch plenty of documentaries, and consume any kind of media that presented these big, life changing trips. “Sure, I’ll have one of those, please!” I thought. And then you’re sitting there on the side of the bed and thinking of all the ways it’s not this perfectly presentable finished product; it’s filled with imperfections. It’s flawed in so many ways. My bike is bent, there’s not a single bag on my bike without a rip in it, my cycling shirt is filled with holes, my shorts, which began their life as a beautiful, dark teal pair are now bleached by the sun, the Buddhist prayer flags that I bought in India to comemorate my decision to embark on the trip are stitched and glued together somewhere between Om and Ma, my second pair of glasses has shattered, there are toolsets that are no longer complete, and even my cooking pot somehow has dents in it. If I pack it all in and go home tomorrow, then this trip will have been one of the best decisions I’ve ever made but damn if it isn’t hard at times.

Tobacco leaves in piles ready for fermentation

Tobacco leaf sorting

The cigar rollers

Some finished product

If I was going to be here for a while I figured I may as well go see the town. On my first pass through these parts I remarked at how many tobacco fields and drying houses I cycled past. Maria-Ines’s son also told me that he works as a cigar roller in Estelí. Cigars are called “puros” here. On one of several walks to the bike shop I chatted with some Americans on the street who were smoking cigars. They recommended the AJ Fernandez tour as the best one around. “Ask for Mario!” So I rode over to the factory one day and talked to Mario, “come back at 13:30” he told me. I guess it’s customary to pay for the tour in US dollars because asking to pay in the local Nicaraguan Cordobas was met with confusion. More generally, a common observation in Latin America is that people can be quite afraid to take responibility for actions at work when there’s a higher up that could then accuse them of doing something wrong. A few phone calls were necessary just to check, “can someone pay in Cordobas?” A few more were made, “what’s the exchange rate?” And a final “Is this amount correct?” A French couple joined us on the tour as their kids waited in the lobby. We were given the option to smoke a cigar while taking the tour, I figured I might as well. When in Rome, right? It was a bit of a bad look walking around the sweatshop-esque factory as one of a few foreigners while smoking a cigar. Next time I’ll be sure to put on some weight and wear a monacle and top hat. The French family offered me a ride back to town in their camper van so I didn’t have to limp all that way. After a cigar on an empty stomach, a short ride down a bumpy road in a hot and humid van, I was nauseous but thankful to be back in town. Another observation is that the families with children that I’ve met travelling, whether by bike or by van, for a longer period of time are always French and the kids always say “coucou” as a greeting.

This guy again

I spent a little less than a week in Estelí. I totally dismantled my bike and inspected it for cracks and bends. In addition to the fork, which was clearly bent I also discovered a bend in the left chainstay one day while eating breakfast and staring at my bike. Roaming around town looking for bike shops, I learned that no one uses the street names or numbers which are shown on Google Maps. Navigation is done using intersections, which are named for a prominent store on that intersection. An example being, “go east two blocks from the La Curacao intersection.” One night I went to a soccer game with some people from my hostel. I rebuilt the bike, which took longer than expected, and hit the road again. Cycling felt better than walking and I took it easy as I made my way to the border.

The city of Estelí is in northern Nicaragua, which meant I was close to the Honduran border, which unfortunately also meant that I had plenty of time to psyche myself out by reading travel advisories about safety in Honduras. It’s the same thing I went through while leaving Quito, Ecuador worried about safety in Colombia. In short, what people told me was that the situation in terms of safety in El Salvador has improved significantly over the past four or five years and those that didn’t get put in prison probably escaped to Honduras. It was incredibly annecdotal information but after you familiarize yourself with one country, crossing a border feels like you have to learn it all over again. That first day back on the bike I made it to the city of Somoto but didn’t find a suitable campsite so I carried on a bit further. I saw some open gates at a ranch and rode down the driveway. Some guys were training horses and said it was no problem to spend the night here; they handed me a beer and pointed me in the direction of the hammock, “go relax.” Eventually most of them left and I stayed with two groundskeepers. I was impressed by their ability to doze off in the hammock as the ranchera music played incredibly loudly.

Roadside spoke replacement

I woke up the next morning as the guys were already busy hearding cattle; not wanting to be a bother I thanked them for their hospitality and figured I’d prepare my breakfast on the road somewhere. A few kilometers later I found a suitable bus stop and started heating some water. A man stopped by on his bicycle and we got to chatting. It was fairly early on a Saturday morning and he stopped at the shop across the street to buy himself a drink. We chatted for quite a while, later we’d even ride a few kilometers down the road together. Back at the bus stop, he told me some harrowing stories of the 80’s when this place was much less safe for a foreigner like me and of his own experiences as a fourteen year old, being given a rifle and being forced to fight in what we know as the Contra War. The drink he bought himself turned out to be a small, plastic bottle of rum that he polished off during our chat. Again it reminded me of how lucky or unlucky you can be with circumstances far beyond your control. He invited me to his house for some soup but I politely declined, I had to cross the border to Honduras today. Somewhere between there and the border I broke my first spokes of the trip. It happened because the derailleur cage hit some spokes. At this point I began to realize that there were some major problems with the bike. I quickly swapped out the spokes and checked their tension by plucking them, trying my best to match the frequency of the new spokes with those of their neighbors.

Honduras

My plan was to zip right across Honduras in about two days and that’s exactly what I ended up doing. I felt safe the entire time and my experiences on the ground didn’t match with the advisories I’d read in the weeks prior. So many people along the road waved at me or gave me a thumbs-up. I stopped for a coffee in a town whose name I don’t remember. Near a border, before and after crossing, I’ll stop to ask a few people here and there how it is ‘round these parts. Most of the time people will tell me the same things (don’t cycle at night, just be careful) and this time was no different. I told the lady working behind the counter about my trip and she just sort of stared at me blankly like I was crazy; sometimes you just don’t connect with people. On my descent down into Choluteca I stopped to buy a drink and chatted with a man named Jose Orban whose grandfather moved to Honduras from Czechoslovakia. We shared some chips. I was fascinated but I had to make it to Choluteca before dark. The descent down to the city at dusk was beautiful.

Entering Honduras

Que vaya bien

Look at you Honduras!

Both nights in Honduras I camped at the Red Cross and both nights they were incredibly inviting. At the Red Cross in Choluteca I cooked together with volunteer doctor Jose; we both had few ingredients but together we made some kind of tasty avocado pasta dish. He was gone early the next morning to go monitor the health of very rural populations and to perform census work, work that he found emotionally draining because of the poverty and despondency.

A billboard for German glyphosate; my first time seeing that

The red Cross in Nacaome, Honduras

I pulled into the Red Cross in Nacaome sometime around sunset and was lucky enough to bump right into the regional chief of the Red Cross Jimmy and his son Jimmy Jr. I was immediately given a Gatorade and we chatted for a long while; I could stay in the volunteer’s dorm with air conditioning and WiFi. They were headed home for the day, Jimmy Jr had some exams to study for, but there’d be more volunteers showing up later. The chaos of showing up at a busy place was all of a sudden quiet and for the next few hours I was the only guy in the building. I listened to the radio chatter for a bit, slightly impressed by my ability to understand Spanish over the radio. I went out and got some dinner, and then went to bed.

Some lost trailers

Honduras ended up being the country I spent the least amount of time in, one full day and two nights. After leaving Nacaome I crossed into El Salvador and turned south toward La Union.

El Salvador

I found it funny how many “Bienvenidos a El Salvador” signs there were; I counted four. In the last five years the country has seen major changes instituted by the government of President Nayib Bukele. I don’t know enough to give a thorough breakdown of Central American history, but unfortunately every country in this region has seen war sometime around the end of the 20th century and gang associated problems. Before reaching El Salvador I met countless non-Salvadorans, citizens of other Central American countries, who were incredibly excited about the presidency of Nayib Bukele and his track record of improving safety and being “tough on crime.” While travelling north I met a few others going south who also had great things to say about El Salvador so I was excited to now have the opportunity to see for myself.

Welcome to El Salvador 1

Welcome to El Salvador 2

Welcome to El Salvador 3

Welcome to El Salvador 4

The official currency here is the U.S. dollar so I hit the ground running with the few that I had left from Panama. My first night in El Salvador I slept on the volleyball court of the fire department in La Union. As users of the dollar I noticed that they referred to 25 cents as a “cora,” which I thought was interesting. I sat on it for a few days and eventually learned that it’s just a loanword, a latinization of the English word “quarter,” which is the term for a 25 cent coin in the United States.

Fairly normal quantities of roadside trash

I spent a rest day at the house of another cyclist named Jose, who spent many years living in Montreal. Many people left El Salvador in the 1980’s to escape a civil war and settled in the United States or Canada. Jose returned in the early 2000’s cycling his way back from Montreal over the course of a year. He told me that it was something he’d said in passing as he was leaving the bar one night and then simply couldn’t take it back. He accidentally committed himself to a cycling trip and he had the time of his life; he’s been hosting other cyclists ever since.

A dusty day in El Salvador

The friendly banana man in El Salvador

Along the road I noticed an impressive amount of billboards advertising remittance services, something I’d never seen featured so prominently. There’s a large diaspora of Salvadorans living in the United States and Canada that sends money home to family i.e. remittances. On another hot day I was taking a break in a shop, having a cold drink, and chatting with the shopkeeper who told me that he very clearly sees which of his customers receive extra money from abroad. About two thirds of his customers don’t look at prices all that much and the remaining third has to budget very carefully. This man was less positive about the recent changes in his country. Whether it’s gangs or the government taking his money through extortion or taxes, he’s afraid to sell his land because he’s scared he’ll sell and not find something new to buy. Regular Salvadorans are being priced out of their own real estate market by a recent influx in foreign buyers, all while an executive branch of government continues to consolidate power. A few days prior I had some beers with a man who told me that in 40 years El Salvador will be the Singapore of Central America. The shop keeper thought that in 40 years they’d be more like Venezuela. I must add that the vast majority of opinions seemed positive but the two different outlooks using two very different countries as examples really left an impression on me. It was palpable though that the country was breathing a collective sigh of relief after many difficult years.

Papusas with self serve curtido, 'big mistake, lady!'

The most iconically Salvadoran dish is a plate of papusas with tomato sauce and curtido. The papusas are a flat cake made of dough (I came across both rice and mais flour) with any variety of fillings like cheese, beans, or chicharon, which is then fried on a big griddle. It’s most commonly also served with curtido, which is a somewhat spicy, pickled cabbage salad. Whenever the curtido was self-serve, as was often the case, I saw it as my chance to load up on vegetables and vitamins. I enjoyed the papusas but I think I enjoyed the curtido more.

An easy morning in La Libertad

I rode through the flat center of El Salvador down toward the coast and camped on the beach for a few nights. I took a rest day with a French couple cycling south from San Francisco. It was good to be able to share the trip with someone for the first time again in a while. Someone did steal my cool Colombian straw hat at the campsite, though. I often took a midday rest in the sanctuary that is an air conditioned Puma gas station. The coffee was always good there and I had a nice call with my parents. It was an uplifting mood boost getting to call and share the trip with others.

Sunset in El Salvador

Drying beans on the shoulder of the highway

After the Salvadoran coast I turned north toward Sonsonate and the Ruta de las Flores. It was a long day of climbing but even just getting to an elevation of 1,500 meters made an incredible difference in temperatures that were so much more enjoyable than the sweaty slog that is cycling in the lowlands. It was interesting to see the forest change to pine trees as I continued to climb up to Eduardo and Romina’s place. I met them via the Warmshowers website and I took a rest day at their wonderful refuge up in the mountains.

Too cool for school

Aside from the obvious downside of climbing on the bike, one particular annoyance is the generous use of “Jake” brakes by tractor trailers. (AKA Compression release engine braking). You know the climb isn’t finished yet when you hear that cacophony continuing in the distance and coming your way. And then eventually here comes the passing truck, a screaming, straight piped, unfiltered, diesel exhaust spewing monstrosity. All hail the macho señor truck driver in his infinite glory. He’s the man. Most people reading this probably live somewhere with strict emissions regulations, especially so for heavy diesel vehicles, and doubly so in densely populated areas, with an additional ban on this type of Jake braking in all but very rural areas. I’ve developed a newfound appreciation for those regulations.

Chicken soup

Feeling good in Salcoatitán

A nice aspect of climbing is that you’re going slowly and there’s more time for people to start talking with you. One lady named Ruth started in perfect English and we bounced around between English and Spanish. She’d lived in Georgia for many years and had now returned home. We chatted for a little bit as she filled a few bags with mangos and some marañónes Japones for me. These kinds of interactions happened frequently in El Salvador as I got the impression that people were very happy to see a new influx of foreigners enjoying their country in relative safety. One day I was eating some mais tamales on the roadside when a couple comes up to me just to chat. “Where ya from? Where ya going?” This type of thing. Again they switched to fluent English because they’d lived in the USA for thirty-something years. They’re also happy and proud to see foreigners enjoying their country and again you sense that the entire country has collectively breathed a big sigh of relief these last few years. They check that nothing bad has happened to you, once more welcome you to El Salvador, and wish you a wonderful trip. After a little more than a week in El Salvador I descended to the Rio Paz and crossed the border into Guatemala.

A downhill, wood hauling go-kart

The wholesome town of Apaneca

An excellent meal. My last in El Salvador

Southern Guatemala

I crossed the natural Rio Paz border between El Salvador and Guatemala at a post called Chinamas. I didn’t know much about Guatemala going in. I had left Eduardo and Romina’s place earlier that morning and it was an easy descent down to the border at the river. Unfortunately, this also meant a return into the heat. Each country within Central America charges an exit tax and this time was no different. The fees have ranged from about US$8 to as high as US$20 to leave Belize. The borders come with varying degrees of bureaucratic theater. I rode to the town of San José las Cabezas and asked at the police department if there was anywhere I could camp safely. Olga, the officer on duty at the front door said it was fine to camp in their impound lot outback.

Crossing the Rio Paz into 'Guate'

Now we're talking

The most peculiar thing I saw that day was a community between Los Hoyos and Las Marias. I had stopped to drink some water when I saw three fully veiled, black figures walking through a field. With no idea what to make of it I just watched them cross the field off in the distance. I rode on a bit further and saw some men in tunic-like clothes walking along the road carrying boxes. There was a large metal building nearby from where they were coming and going. I stopped to ask a local man who they were and he told me it was a Jewish community. I asked some more questions, we chatted a bit, and then I kept on riding. I was about five kilometers down the road when I decided I couldn’t keep going without learning more so I turned around and rode back up the road. I stopped at a small shop where a local man offered me a beer, it was almost 5PM but I declined. I asked one of the traditionally dressed men if he spoke English, which he did fluently. They speak Yiddish in their community and after telling him where I was from we admired the similarities between Dutch, German, and Yiddish. A few times I asked him if his community had a name but he simply said that they’re Orthodox Jews.

Not sure what happened here

An Orthodox Jewish man

The next day I carried on along a fairly busy road, eventually turning off and heading down a quieter gravel path. I climbed up and over a ridge and descended down toward Lago Amatitlan. Toward the end of the afternoon now, it was time to look for a campsite so I bought some fruit from a roadside stand and chatted with the sales lady and some cops that were standing there. They said there were plenty of villages up ahead. It was proving a little difficult that evening so I asked an “auto-hotel” where they rented rooms by the hour. No thank you. Prominent in conservative Central America seem to be these types of hotels that advertise hourly rates and hidden parking lots behind garage doors, I guess to prevent your car being seen by acquaintances. So I kept riding and found a church on a large plot of land but no one answered when I knocked. Again I kept riding. It was now well past sunset. Eventually I reached another village where some ladies were cooking in front of their houses. I stopped to ask if they knew of any places where I could camp for the night as some kids looked down curiously from the upper floor. “Ride down to the basketball courts by the church and ask for Don Beto,” she told me. So I rode the few hundred meters to the courts and asked a big crowd outside the church if they knew where he was, upon which they all pointed at a man walking our way. It’s a wonderful feeling, that sudden sense of relief after you feel the night creeping in around you and go from uncertainty to certainty. Don Beto was a big, cheerful man, he shook my hand and said he had a spot for me. I waited for mass to finish, lit some dangerously large fireworks with some kids, ate dinner, had a few churros for dessert, and slept soundly in the church rec room.

A mural of your truck, on your truck

A lot going on in this bus

I was now cycling along the southern edge of Guatemala City and could sense the increase in traffic density. I stopped for a mid-day coffee and McFlurry break at McDonald’s before starting the large climb of the day toward the city of Antigua. It was not a nice climb. I had a shoulder but the road was congested with truck traffic and the subsequent pollution. I rode past a few incredibly large garbage dumps where there were school aged kids sorting trash and riding on the back of the garbage trucks. The road became so busy and congested that traffic slowed to a crawl. This meant that there wasn’t much room left to cycle so I took a break on the side of the road under the shade of a tree. A man named Roman stopped and offered me a lift toward the intersection at the top of the hill. From there it was pure descending down into Antigua. Antigua is a beautiful, old colonial town which was once the capital of Guatemala during the rule of the Spanish empire. Picture beautiful colonial architecture and, from my perspective, horribly cobblestoned streets. Naturally, it’s a tourist hotspot so there’s good pizza places. Not wanting to mess with tradition, I went and had some pizza on arrival. One of the thoughts that comes up again and again on this trip is economic inequality. Yes, Latin America is economically less developed but it also seems less egalitarian. Less than twenty kilometers away, away from the relative affluence of a touristy town you get passed by garbage trucks with twelve year olds hanging off the back during what should be school hours while here there’s expensive cars and cyclists on $10k road bikes whistling at you. I don’t know what to make of it. How lucky am I that I was born where I was born and to whom I was born?

Up above the clouds now

Volcán de Fuego exploding. Thanks, Binni for the photo!

I took some time off of the bike and rested while in Antigua. My leg was starting to feel a lot better, recovering from the accident. I walked around the city, ate lunch at the market most days, and drank lots of coffee. I stayed with a German cyclist named Thomas who, after spending six years cycling around the world, is now living in Antigua. We shared stories from the road over many good meals. A few other cyclists came and went and enjoyed the conversations with them. There was a swiss cyclist couple Clement and Gaia, a Belgian cyclist coming south from Alaska named Francois, and a German cyclist named Binni (you can check out his website here). Together with Binni I hiked to the summit of a nearby volcano from which you can see the Volcán de Fuego, which erupts very frequently and magnificently. Thomas told us of a spot where you can camp for free high up on the volcano and with clear weather, at night, you get a spectacular show. Binni and I packed a dinner, took two buses to the trailhead, and began hiking in the late morning. We reached our campsite toward the end of the afternoon and could hear what sounded like rolling thunder in the distance. Eventually the clouds cleared after dark and we bore witness to one of the most spectacular natural phenomena I’ve ever seen. Huge explosions of lava shooting high above the open summit of the volcano; it was a volcano the way you’d picture a volcano. It was incredible! We hiked the rest of the way up to the summit for sunrise and then made our way back down to the road to catch the bus back to Antigua.

Volcán de Fuego in the morning

The view from the summit of Acatenango

The busy summit at sunrise

Volcán de Agua at sunrise

A brush fire seen from Thomas's apartment

I stayed two more nights at Thomas’s place before hitting the road headed for Lake Atitlan. On my first day back on the bike, just out of Antigua, I stopped at the Temple to San Simón (AKA Maximón), a folk saint and an interesting example of religious syncretism between indigenous Mayan beliefs and imported Catholicism. Outside the temple, people tend to thick, black, billowing fires and ceremoniously smoke cigarettes and cigars. Inside there’s a line to visit the shrine, you can pay the mariachi band to play a tribute, and the walls are covered with framed pictures and plaques, messages of thanks to San Simón. The messages of thanks are for things like health and wellness but also for things like a car or a motorcycle or for a family member’s safe passage to the United States. I thought it was an incredibly interesting glimpse into Guatemalan culture.

Cathedral San José in Antigua

La banda at the templo de Maximón

Outside of the temple

Tuk tuk culture

The first night back on the bike I camped at the fire department in Patzún. The little bit of altitude that I’d gained throughout the day made for a much nicer climate and the following day I descended down onto Lake Atitlan. I wasn’t sure why I’d come this way aside from the recommendations I’d received from other travellers. I took a boat across the lake to San and then rode the rest of the way to San Juan where I spent the night. The following morning I decided I wanted to take a bus back to Guatemala City so that I could visit Belize and the Mayan temple complexes of northern Guatemala. As the school bus makes its way toward the stop where you’re waiting you can hear it several minutes out as it blazes its horn. I quickly haggled on the price a bit, we agreed on a price, the man took my bicycle, yelled for me to get in the bus as they’re always seemingly in a massive rush, flipped the bike on his back, climbed the little ladder on the back of the bus, and off we went. In between stops as we were driving along he was still on the roof tying my bicycle down to the rack. The normalcy of this entirely different safety standard was a bit jarring. I made it to Guatemala City a few hours later. Francois, the cyclist coming south from Alaska and headed for Ushuaia, had share the number of Cesar with me. Cesar runs a casa de ciclistas in the city where he hosts cyclists as he waits to set off again on his own long distance trip. I reminisced about my time in Argentina together with a couple from Buenos Aires that was also staying in the house. That was night 456 of my trip and I thought back on those first weeks and months in the saddle and what an experience it’s been. It feels like a lifetime ago. Drinking mate, eating alfajors and facturas, enjoying steak and wine, beginning to learn Spanish, their wonderful accents, and of course long days of riding into big skies and stronger headwinds. Sometimes it feels like a time I wish I could go back to just to relive it all again.

A trash strewn hillside

Up, up, up

And then down to lago Atitlan

By day everyone had their errands to run so I headed off with Cesar to search through a chain of second-hand stores called Megapaca. Cesar needed a new thermos before he set of cycling again and I needed a new water bottle after losing my own on this latest bus trip. Cesar scored big by finding a vintage Stanley thermos and I found a nice Specialized water bottle that must’ve been handed out as a promotional item by the Schlitz Audubon Nature Center in Wisconsin. It struck me while rummaging around the items how much of it seemed to have been donated from the United States. Just a small peak and I found old little league jerseys with players’ names across the back, a commemorative mug for some program involving the Baltimore City Police Department, a finisher’s shirt for the 2011 New Paltz Turkey Trot, a sweater for the 2018 graduating class of Dakota Valley High School, and the stuff went on and on. So much stuff. Stuff that gets made and discarded without much thought as we’ve seemingly forgotten the reduce and reuse aspects to “reduce, reuse, recycle.”

My bike on the Atitlan ferry

Sunday night in San Juan

Plaza de la Constitución

A giant relief map of Guatemala

Guatemala: mountains in the south, flatlands in the north

We also walked around together as a big group a few times as Cesar gave us his tour of the city. I think my favorite part was an out of the way, giant relief map of Guatemala. Noticeable was the stark difference between the mountaineous south and the fairly flat, forested north. While I was in Guatemala City there were several water outages where there was simply no water. When there was water we’d collect it in large basins and take showers. On one of our walks past an appliance store I saw that there were washing machines that were advertised as manually fillable for when the water goes out.

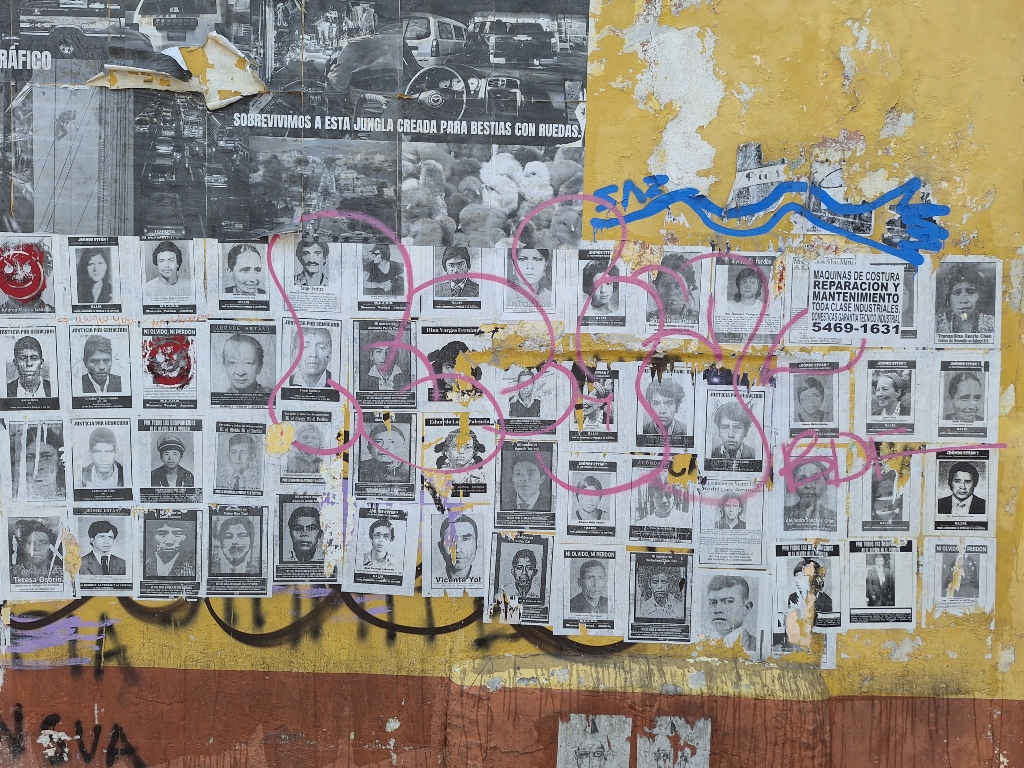

Missing persons

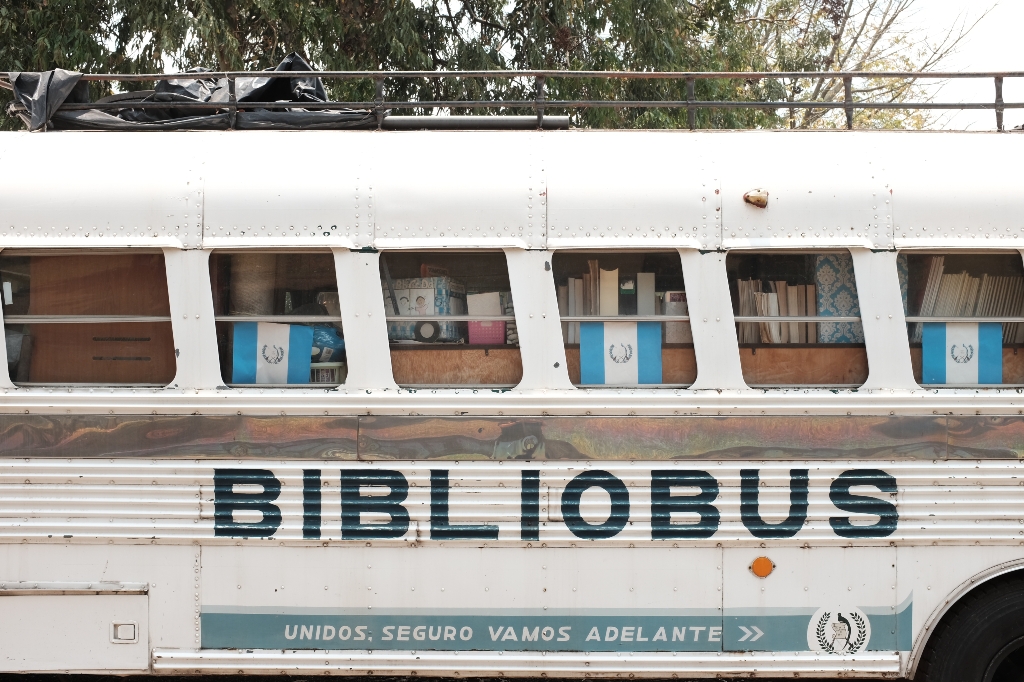

The cool bus

The gang keeping Guate City welcoming

After three nights in the city I said bye to the group and took another bus further east to Puerto Barrios. I camped at the fire department in Puerto Barrios where they had a Mercedes Benz 1622 firetruck that was donated by the Netherlands. The guys were very excited to show me. After one night’s rest there I exited through Guatemalan customs and took a boat ride across the Amatique Bay to Punta Gorda, Belize.

Graffitied street corner

More missing

Cool design work at the national library

Pizza, pizza!

A washing machine advertised as manually fillable

Bomberos in Puerto Barrios. The Mercedes 1622 was donated by the Netherlands

Big banana boats

Crossing the Bay of Amatique to Belize

Belize

Belize is the first English speaking country I’ve visited on this trip and that took some adjusting. Customs was fairly strict about entering with fruit or vegetables and I was interested by a poster that showed the permissable quantities of single use plastics that could be brought into the country. “No more than 10 plastic bags and cake domes by permit only.” I had lunch of stewed chicken in Punta Gorda, which was seasoned much differently than what I’d come to expect in Latin America. Belize was interesting for its more Caribbean atmosphere and Creole English language. The country also proved to be significantly less densely populated than the other countries I’ve cycled through recently. Not finding any spots to stop for an afternoon coffee, I setup shop in a bus stop and was quickly joined by a man named Barry waiting on the bus. We chatted about Belize and the coming rainy season, which seemed to be a month later than what I’d been hearing in Guatemala. We spoke English together but when Barry’s friend showed up to also say hi, I couldn’t make out but a few words between them as they switched to Creole.

On the dock in Belize

Belizean customs building

Do you have permit for that plastic cake dome?

A bus stop

I spent the rest of the day riding to the Ya’axche field station where for a small fee they had a campground where I could setup my tent. As I was leaving in the morning I noticed some rattling coming from my rear derailleur and stopped to check it out. After the crash back in Northern Nicaragua I’d been having problems with my gears; I think the derailleur was also bent somewhat in the crash. So that morning I tried to bend it back into alignment slightly and it went snap! That’s no good, I thought. I found a shady spot out front and had a think about what to do. Thank God it’s flat here, at least I’ve got that going for me. I figured the only real option was to convert the bike to a singlespeed and go from twelve gears to one. Simple. My first task was to “break” the chain. Most chains these days have one special link that can be opened but this takes some effort as this link spends so much time being pulled closed as you’re pedalling that it gets pretty good and stuck. By the time I got to this point most of the guys from the ranger station had come out to see what I was up to. A few hung around and observed. They spoke an indigenous language, I think Qʼeqchiʼ, and I could only make out the odd word here and there, like “bicycle.” Eventually all but one went back inside. The remaining guy sat on a bench behind me and said nothing. I could hear his feet swinging in the tall grass beneath the bench. I struggled to break the chain in the late morning heat when he finally breaks the silence with “it’s hard, no?” All I could do was laugh and think “nah I’m just foolin’ around before I get to work!”

It's not supposed to be like that

Singlespeed with wooden stick chainguide

Eventually I was able to hit the road again, this time travelling a bit more slowly as I sometimes had to push up hills and sometimes couldn’t pedal any faster. But I was moving! I had to stop by the roadside to put a tube in my front tire as the tubeless system kept struggling to seal a small hole. I hadn’t opened that front tire up in a long time and the valve was corroded and stuck in place. I spent about an hour by the roadside struggling with my little pliers but no one was stopping. Eventually a small group of workers from the nearby banana plantation came over to see what I was up to. I explained the problem, a few of them gave it a shot but they quickly realized we needed bigger wrenches. One went off and came back with the proper tools and we were able to remove the valve and install a tube. I was off and riding again thanks to their help. I made it to Independence and got to talking with Rudy who said I could camp in the unfinished gazebo in his backyard. On my first day in Belize I noticed two things. There’s way less roadside litter than in the other Central American countries and it felt safer. I’d noticed in the last few countries that big, luxurious houses often had massive walls with barbed wire and security systems surrounding them; these fortresses make the whole place feel less safe, but in Belize there were also pretty nice houses that didn’t have such features. Rudy’s backyard also wasn’t fenced in and felt totally fine for a good night’s rest.

Sparsely populated Belize

'This the for we chicken' translates to 'this is our chicken'

The next day I left Rudy’s backyard early and took the Hokey Pokey ferry from Independence down Mango Creek. The English place names again required some adjusting. I saw a manatee from the ferry boat. From Placencia I carried on northwards along the beach. This part of Belize was quite touristy. Thankfully the road was pretty flat but the cycling was still difficult in the heat. Sometime around midday I decided to stop and go for a swim at the beach. As I stopped and turned around my front tire slid somewhat in the sand and I almost fell but caught myself. Just then, a collectivo van was slowly driving by and a lady hollered from the back, “if ya fall I’m gonna pick ya up!” I couldn’t help but laugh. A few days later I was sheltering from the heat in a bus stop and using the time to do some journalling. Another van drove by slowly and a lady asked from the back, “are ya writin’ ya numba down for me?” I’m still laughing about that one, too.

I'm curious what Mexican insurance is

Riding the hokey pokey ferry

The rest of the day’s riding was fairly uneventful; flat and sparsely populated with not a lot to look at. I spent a rest day with Gary in Maya Centro learning all about epiphytes and other varieties of tropical plants. The next day I got a very late start headed toward the Hummingbird Highway. I didn’t make it far and spent the night camped out near a school in Pomona. The highway itself was quite beautiful. I stopped for a swim in the cool waters of the “inland blue hole,” a source of cold water rising out of a deep underground cave system. Here and there I had to push up some long hills but eventually I rode into Belmopan and headed for the firehouse. I was greeted by fire chief Chen and was two sentence into my usual speech when he interjected and asked, “you wanna camp out back?” We both had a good laugh. Shortly after my arrival the power went out for the rest of the evening. This had happened the past several nights at the school and at Gary’s house but I was surprised it went out for so long in the capital city. The following day I rode the rest of the way to the border and returned to Guatemala.

A cool swimming spot, the inland blue hole

Donated by Taipei, Taiwan at the Belmopan fire department

The Mayan ruins of Northern Guatemala

My first night back in Guatemala was in the small city right by the border, Melchor de Mencos. Again, I was camped next to the fire department and spent the evening chatting with Melchor who had just gotten back from a call. There was no one around when I first showed up. The following morning was Friday and I was awoken around 04:45 by a truck driving around the neighborhood playing loud music, making announcements of some kind over a loudspeaker, and lighting packets of firecrackers. My first thought was “are you serious?” But I asked Melchor in the morning and it was a celebration of Día de las Madres, Mother’s day. What a start to the day!

That part's also not supposed to do that

Roadside fix by Gaspar

The north acropolis at Yaxhá

In addition to seeing Belize, my reason for travelling back this way was to see the Mayan temple complex at Tikal. First, I went to see another archeological site called Yaxha, which was recommended by another cyclist and equally impressive. After an easy morning at the nearby by campground, I chatted with some workers who were painting signs for the park and they watched my bike while I explored the temple complex. What I liked about Yaxha was that it felt like I was the only guy there. Occasionally I met another group of tourists but it felt like I had the place to myself. Upon return to the bike the guys sold me some lunch and I hit the road again. I limped the bike back to Flores and elected to take a organized tour from there to Tikal. Cycling in this cobbled together singlespeed setup really hasn’t been much fun. Turning a corner and seeing even a slight hill hits pretty hard in this 40 degree heat.

Red, hazy skies in Flores caused by nearby forest fires

She's seen better days

I enjoyed seeing Tikal and its famous temples but it’s something better seen in controlled doses. The amount there is too see almost becomes overwhelming. Beautiful temple here, big pile of stuff there, ball court over there. It reminded me of how I felt seeing the many Incan sites in Peru. I was happy to have come this way, though. I took a tour which started just after sunrise in an attempt to beat the heat. I met a friendly English couple on the tour and together we went and had some dinner that evening. I spent a few more days in Flores roaming about and then hit the road again headed for the Mexican border, which will be the last “new to me” country of the trip.

Temple 2 at Tikal

The sun appearing behind temple 1

Temple 1

Temple-tops peaking out above the forest canopy at Tikal

Temple 5, my favorite